Inviting Students to Share their Understanding

By Carla Marschall

Imagine your classroom: What are your students doing? How are you gaining an insight into their learning progress? Given that international, national or state curricula often “zoom in” on the knowledge and skills students should acquire, we typically look for evidence of discrete knowledge or skill development in our classrooms. We may ask students to write, take a quiz or create products that illustrate knowledge or skills in action. But where does this leave understanding? How do we know that students can transfer their learning to new contexts? With the dawn of the age of automation, we owe it to our students to help them construct and express their conceptual understandings in an explicit way in the classroom.

What do we mean by conceptual understanding?

Within a Concept-Based Inquiry approach, we describe conceptual understandings as statements of conceptual relationship that contain two or more concepts (Erickson, Lanning & French, 2017). The forming of understanding requires students to make connections or links between concepts, as well as ground their abstract ideas in concrete knowledge or skill learning. In this way, understandings go beyond facts and articulate transferable ideas. Depending on the program you are using, conceptual understandings may be known by other terms, such as: generalization, central idea, statement of inquiry or essential understanding. We also keep in mind a set of criteria when constructing strong conceptual understandings:

- We write them in third person, e.g. it, they, their, so statements transfer across time place and situation.

- We avoid weak verbs such as is/are, have, impacts, influences and affects to make relationships between concepts clear.

- We use active instead of passive voice to make relationships between concepts clear.

- We use qualifiers like can, may or often if required to make a statement true.

- We do not include judgements or values to keep a statement true.

Here are a few examples and non-examples to give you an idea (concepts in bold).

Conceptual Understandings:

- Authors consider their audience and purpose while constructing a text.

- Ecosystems require a dynamic equilibrium between producers and consumers to thrive.

- Factorization decomposes a composite number as a product of simpler factors.

Not Conceptual Understandings:

- The writing process is dynamic and flexible.

- The world changes, yet also stays the same.

- Numbers are made up of other numbers.

As we can see, the conceptual understandings in the left column contain two or more concepts, while those in the right column do not. Furthermore, many of those statements in the right column use weak verbs such as is/are or are constructed in passive voice.

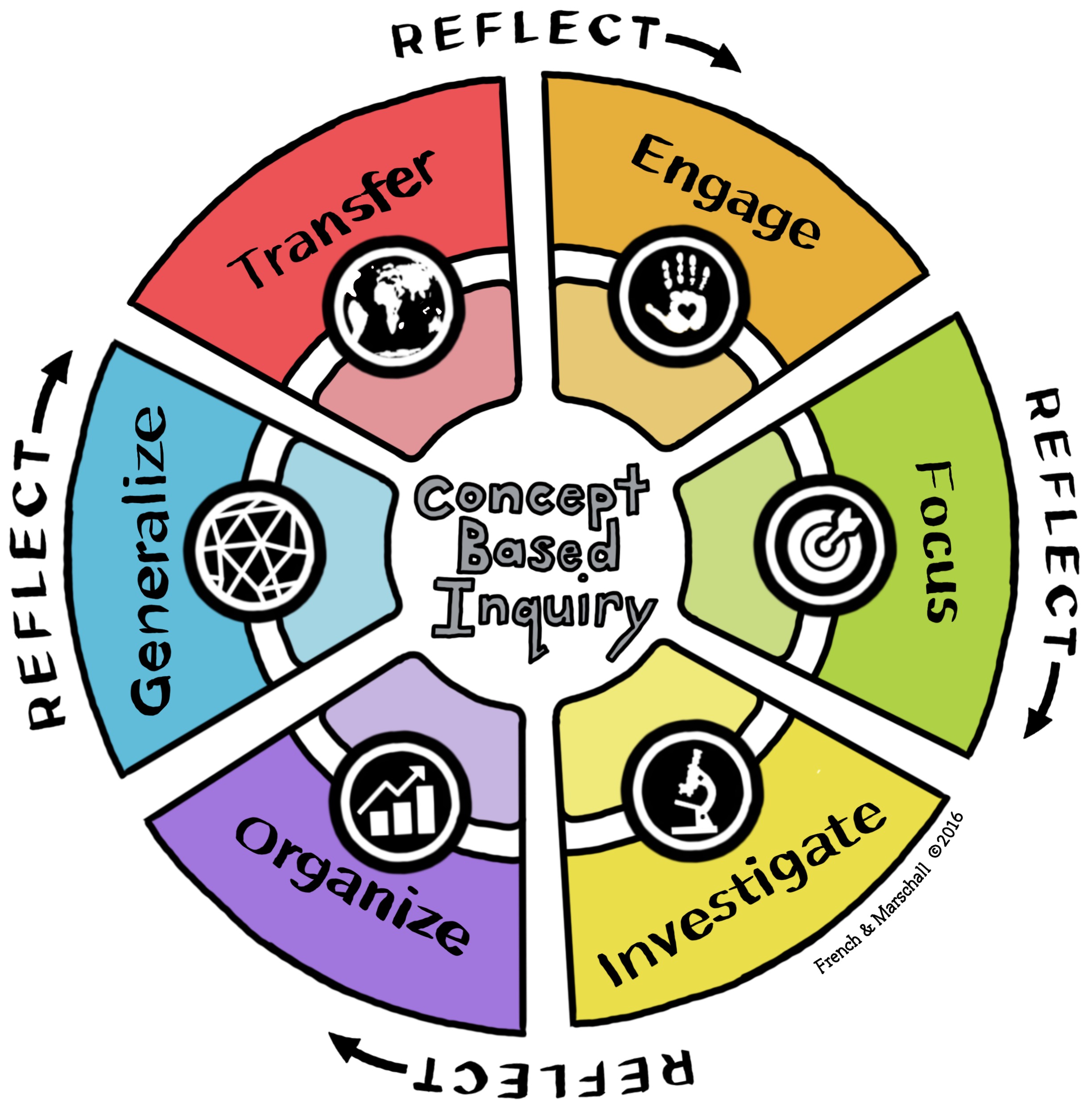

Should students share their understanding in every inquiry?

For students to identify patterns in their fact or skill learning, they need opportunities to extract significant ideas in each inquiry. This process takes learning at lower levels of thinking and raises it to higher, more abstract levels. Within a Concept-Based Inquiry approach, we refer to this phase of inquiry as Generalize. In the Generalize phase, we ask students to look for connections between concepts and articulate their thinking as conceptual understandings.

Source: Marschall and French, 2018

Why do we include this phase in every inquiry? We want students to own their thinking. If we share our understandings with students at the beginning of a study, for example through “unpacking” a central idea, we limit the diversity of classroom thinking and take away students’ personal agency. We want each student to have the chance to state their own understandings, which may be similar or different to their peers. Through discussion, our students can find commonalities across their ideas as well as consider what counts as “strong evidence” to back up their thinking.

It is important to note that the process of generalizing is often not easy for students. It is challenging, cognitive work. However, the process of expressing one’s understanding develops thinking skills, which get progressively stronger each time students exercise them.

What does it look like for students to construct and express their own understanding?

In Humanities, my Grade 7 students recently studied the Middle Ages in England and France. A topic traditionally locked in time, place and situation, I thought at length about how to help students form transferable ideas using this content. One way was to ensure that learning about the Middle Ages in England and France was “paused” every now and again to consider other contexts and situations.

After learning about English feudalism, a social structure, I wanted my students to consider other social structures from the time and how they shaped interactions between groups of people. I gave my students two other case studies to choose from that looked specifically at the role of social structures in society: the Tang Dynasty (China) or Viking society (Scandinavia) during roughly the same time period. Learning was organized using a cross-comparison chart that used concepts and factual questions as headers:

|

Land System How was land ownership organized? |

Taxation

How were people taxed within society? |

Social Stratification

How was society structured? (e.g. classes) |

Rights and Access What rights and access did different members of society have? |

After reading a chosen case study and sharing their learning in groups of three, I asked students to color code and annotate their cross-comparison charts to look for any links across the social structures of the three societies. Then I asked them two conceptual questions:

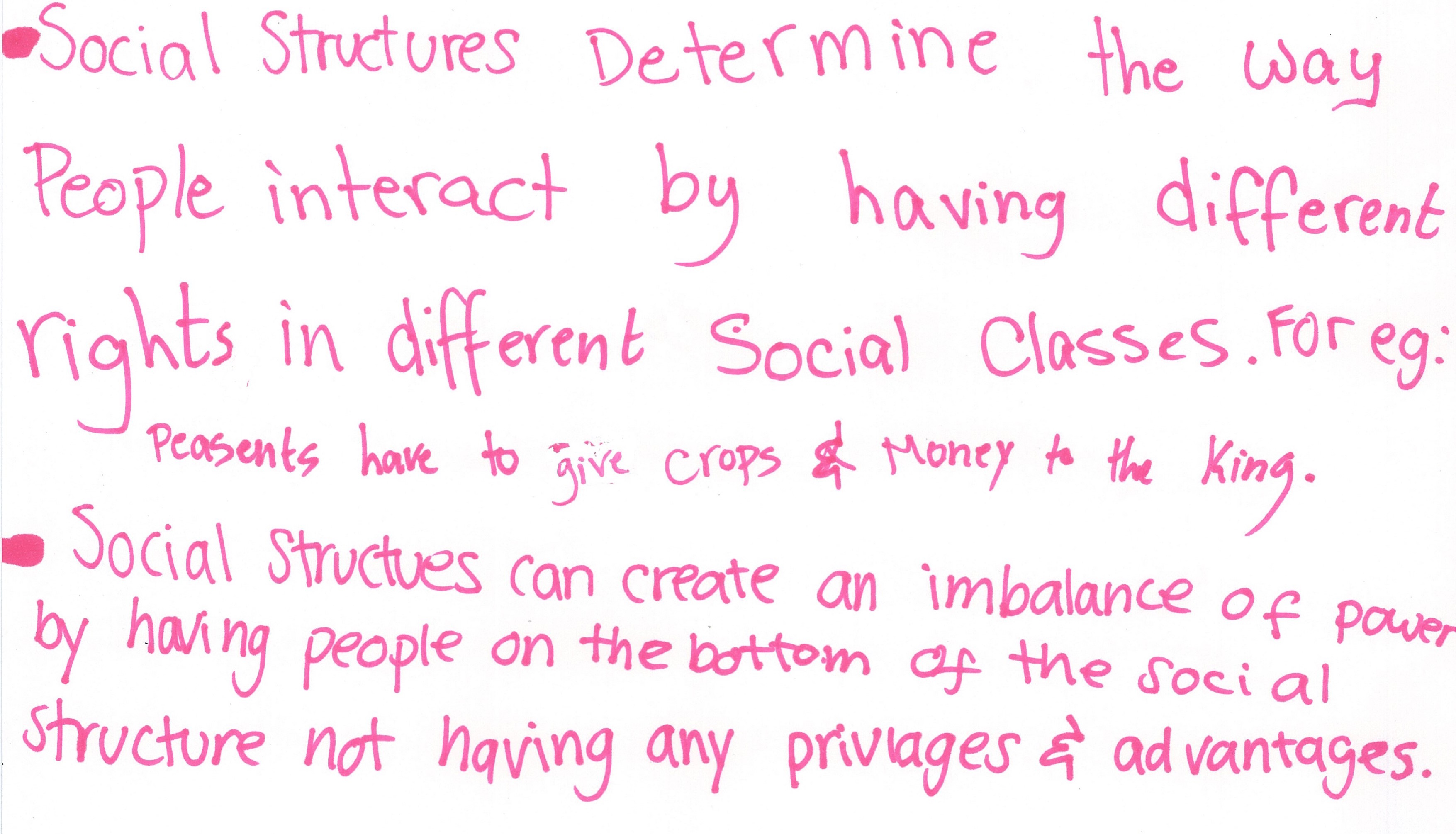

- How do social structures determine how people interact?

- How might social structures create an imbalance of power?

Using their findings from the cross-comparison charts, students then generalized. Some groups needed sentence starters such as, “Social structures can create an imbalance of power by…” in order to write their statements of understanding. This is completely fine, and is an appropriate accommodation for students learning how to think abstractly! Most importantly, ideas came from my students that belonged to them and reflected their learning. It provided an excellent opportunity for me to see what “stuck” from the study and how deep their individual learning went. Here is one group’s thinking:

After students wrote their ideas, we had a thought-provoking conversation about the concept of “social class” and whether or not they believed it still existed today. My students were very animated, exclaiming that, “Although people aren’t serfs or barons today, the very poor and the very rich do not interact often with each other in society today.” This conversation showed me that students were developing transferable ideas that they could use as critical thinkers to analyze and understand the world today, one of the true goals of education.